Some of the restrained, Zen-like commands (such as “Leave a piece of canvas or finished painting on the floor or in the street”) had already been realized, by Ono, at the time of the book’s original publication. The original “Grapefruit” is split into five sections-Music, Painting, Event, Poetry, Object-with each page offering a conceptual direction for work yet to be created. This gets to the heart of what Ono and some members of the Fluxus movement were up to. The viewer is asked to hold both the notional sketch and the “finished product” in mind, without choosing one over the other. We don’t have to lament the loss of “hard” objects such as paintings or sculptures-those are in the next room over. But something remarkable happens when Ono’s manuscript is placed alongside her paintings and sculptures: at last, we have a chance to see the continuum of Fluxus-era artistic practice in full, incorporating everything from an initial idea to the provisional executions of that same thought. (At the exhibit, all the pages from an early copy are posted around the perimeter of a large gallery). Seeing the original edition is rare enough: copies of the first printing have been scarce for decades.

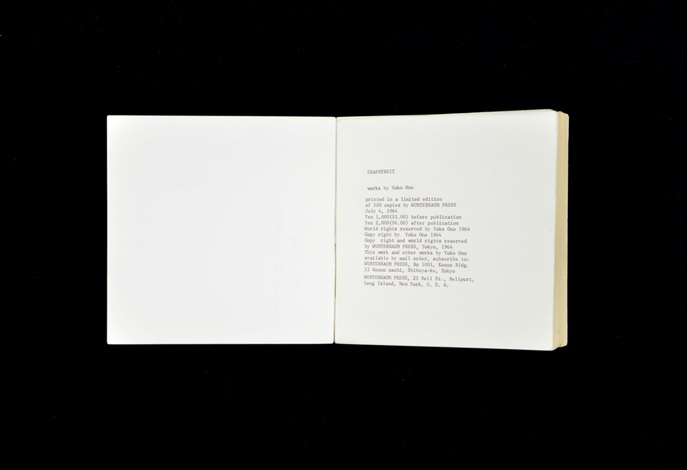

It’s precisely this inevitable erasure that makes MOMA’s decision to devote an entire gallery to a single Ono book-“Grapefruit,” her 1964 compendium of conceptual-art instructions-feel so crucial and rewarding.

#Yoko ono grapefruit analysis of handpiece 1963 summer series#

Since Maciunas himself didn’t attend the series in 1961, Ono closes with a recommendation: “Don’t talk about what you don’t know.”Īny collective as puckish and as taken with impermanence as Fluxus naturally flirts with the loss of primary-source documentation. “You shouldn’t write as if La Monte Young was the producer just because he has taken the credit for it,” she writes. Included in MOMA’s exhibition book is a 1971 letter from Ono to the Fluxus ringleader George Maciunas, in which she sternly and righteously asserts her role in the programming that took place at her loft. And as with other suddenly historic modern-art scenes (such as Andy Warhol’s Factory), credit-taking regarding who-did-what-exactly complicated the relationships among key artists who might otherwise be pooling their archives. Some of the composers Young championed at Ono’s loft, such as Terry Jennings, have tantalizingly slender discographies. Images and audio documentation of this period fall far short of what one would like. Even Duchamp himself paid a visit to 112 Chambers Street. By providing a place for such a diverse range of post-Dada practices, Ono became a one-woman force, a potent curator of New York’s downtown scene. In 1961, Ono’s loft was the place to catch mixed-media performances starring a variety of names that would eventually become counter-culture legends, including the composer Terry Riley, the Fluxus artist Alison Knowles, and the contemporary-classical-piano virtuoso David Tudor. In MOMA’s opening galleries, you’ll find recreations of Ono’s conceptual, audience-engaging works, such as “Painting to Be Stepped On,” and photos of Ono dancing with Robert Rauschenberg, or hanging out with the first-generation minimalist composer La Monte Young (whose programs for a music series hosted at Ono’s loft also line one of the gallery walls). From there, though, the museum turns back the clock, recreating the 1961 world of Ono’s much less talked-about-and arguably more important-New York loft, at 112 Chambers Street. MOMA’s “Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960-1971,” which opened last week, allows audiences just one John Lennon-conjuring piece at the entrance: Ono’s 1966 fruit-on-Plexiglass-pedestal sculpture, titled “Apple.” Depending on your record collection, the object may call to mind the Beatles’ recording imprint of the same name, which launched in 1968.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)